If you play the word association game, and ask someone to come up with the first word that enters their head when you say ‘Urban’, surprisingly enough, the answer is not ‘Ecology’ in much the same way as if you say to someone ‘European’, they do not say ‘Landscape Conference’. If you put ‘Urban’ into Google, this is the image that comes up as number one.

If you play the word association game, and ask someone to come up with the first word that enters their head when you say ‘Urban’, surprisingly enough, the answer is not ‘Ecology’ in much the same way as if you say to someone ‘European’, they do not say ‘Landscape Conference’. If you put ‘Urban’ into Google, this is the image that comes up as number one.

In fact the first two hundred or so images are nearly all either glossy (shiny glass, steel, night shots) or gritty (traffic, graffiti, urban decay). People make brief appearances here and there. Urban parks make their first entrance – actually the first representation of a tree – at image number 46. At around number 240, a subtle shift occurs and ecology, water resources, and urban agriculture not only all make appearances but then feature strongly in the following returns. It is almost as if when you ask people to think of urban, they first think of the non-human aspects, then the human – side and finally natural features. So clearly, we tend to think of cities as dense, built environments, with people coming second and the natural world coming in somewhere way down the field. And yet despite this, as recent studies have shown – iTree amongst them – London is 52% green or blue with most other UK cities doing at least as well if not better.

aerial photograph of Belgravia London England UK

an aerial view of London

The left hand photo of Central London show as much green as grey; this of course shows some of the more affluent parts of the city. Indeed the word ‘Leafy’ is synonymous with affluent. In fact, as the right hand picture shows, the green/grey ratio holds up pretty well across the urban grain.

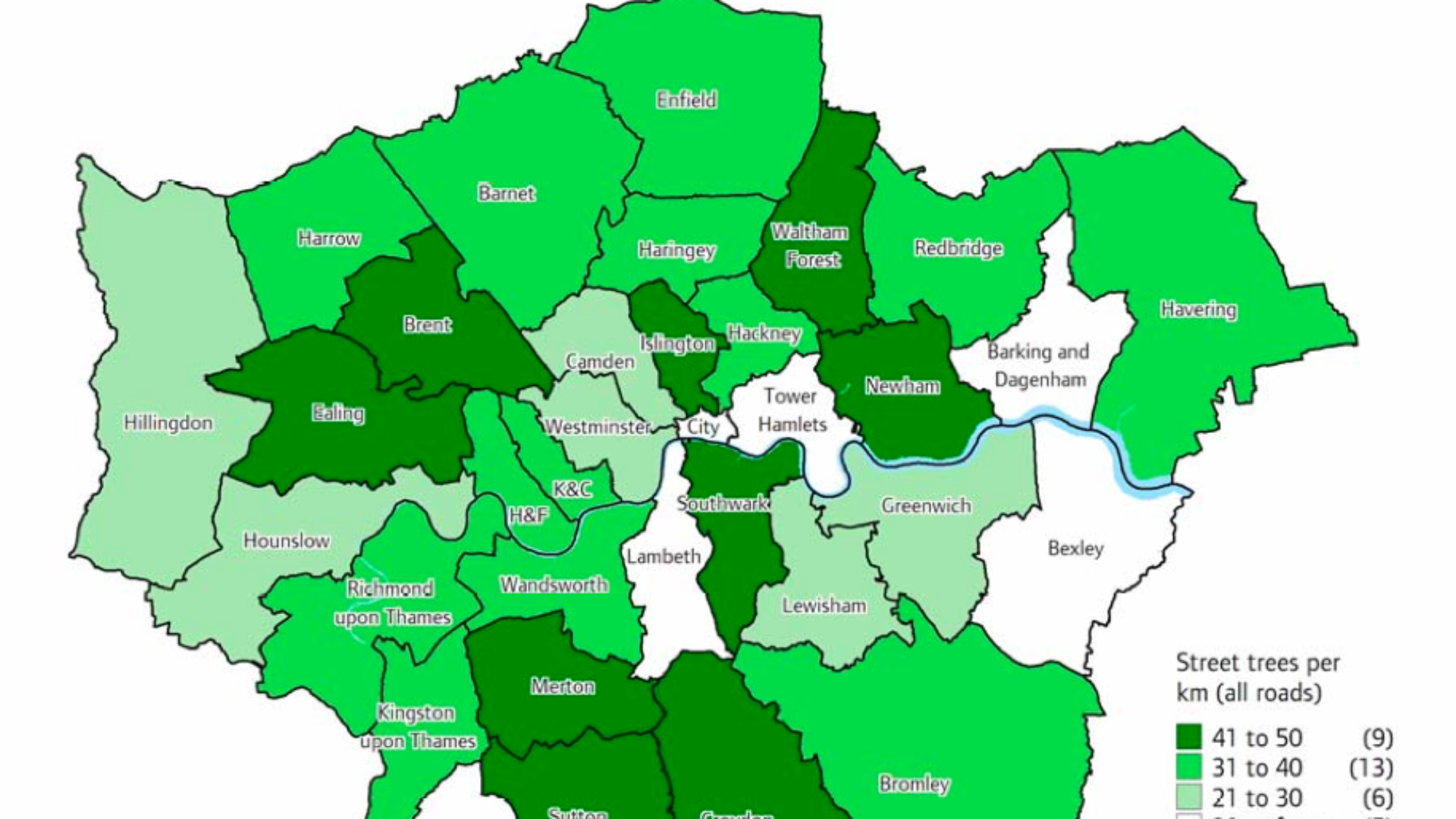

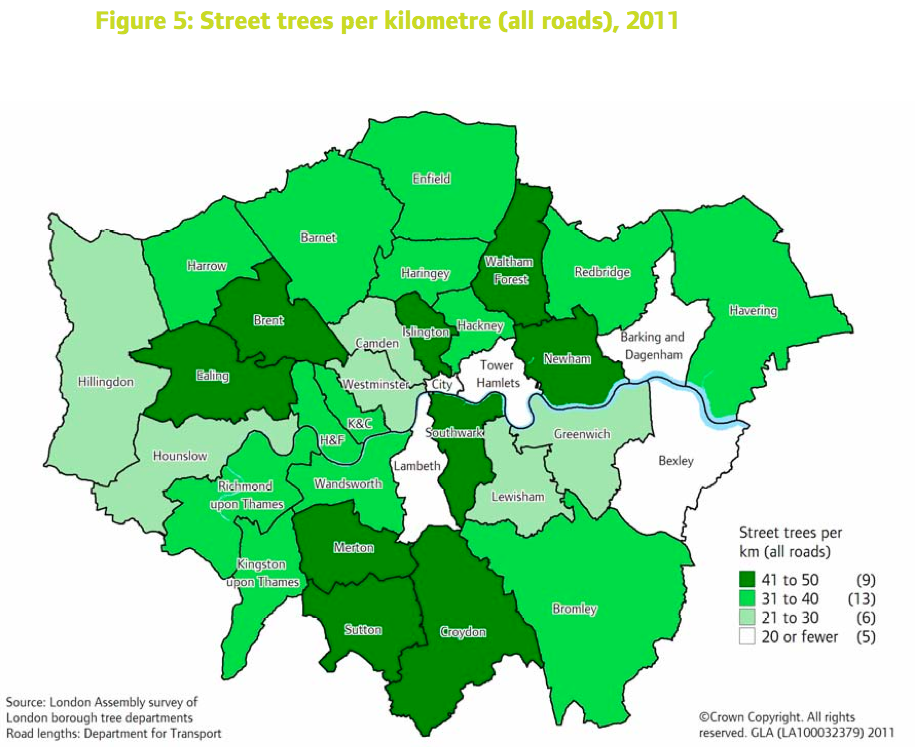

Look at this map of London – it shows the density of street trees. The interesting thing about this is that apart from the obvious – fewer trees in the city of London for example – there is no clearly predictable pattern, which suggests it is more about policy than topography or other factors.

Look at this map of London – it shows the density of street trees. The interesting thing about this is that apart from the obvious – fewer trees in the city of London for example – there is no clearly predictable pattern, which suggests it is more about policy than topography or other factors.In fact, the relationship between gardens, ecology and landscape is not only very old; it is intrinsic. What is the oldest garden you can name, other than the Garden of Eden? The answer is of course the hanging gardens of Babylon. Cities came about with the development of organised agriculture, on a scale which allowed specialisation. This in turn led to spare time and resources for elites. Gardens, both public and private, were a natural and inevitable development. These are well documented in Mediterranean and Middle Eastern cities, but also in China and South/Central America. Although medieval cities were often very dense, during the C18th and C19th, cities began to develop a more intentionally porous character. Garden squares, church yards and left over market gardens all became absorbed into the urban grain.

Everyone’s dream house?

During the C20th, the emergence of the Garden City movement in Hertfordshire, Merseyside, Birmingham and London added a new dimension to these public spaces. For the first time, private gardens en masse became a feature of cities and laid the pattern for modern suburbia. It was everyone’s dream to have their own house, with their own front door and their own garden. Of course, private gardens can be rich and diverse ecosystems.

The more we pack into a garden the richer the biodiversity.

Gardens are per se good, but the more diverse the environment, the richer the ecosystem. The less we intervene, the better: untidy is good. So, in many ways this suburban movement has brought advantages for ecosystems, but as the density of development has increased, all too frequently what we end up with is this: *. Tiny patches of grass and slabs with no shrubs or trees, and a sterile ecosystem. There is a strong argument in favour of creating even higher densities, and combining them semi-public communal spaces. This allows the creating of meaningful chunks of dense landscape for everyone to enjoy. Look at these examples from Darbourne and Darke’s work in the 1960s that I took on a recent visit to the Pimlico estate.

Lillington Gardens Pimlico, by Darbourne and Darke

And yet recently, in city centres we seem to have lost the plot completely. When it comes to public space, we frequently end up with Sterile spaces. An endless recreated pastiche of about four elements that you will all be familiar with: box hedging, black granite or basalt, plane trees, sterilised water features. In London, a city driven by money and commercial power, the primary goals of restoration are twin (and linked) aesthetic, and return on investment.

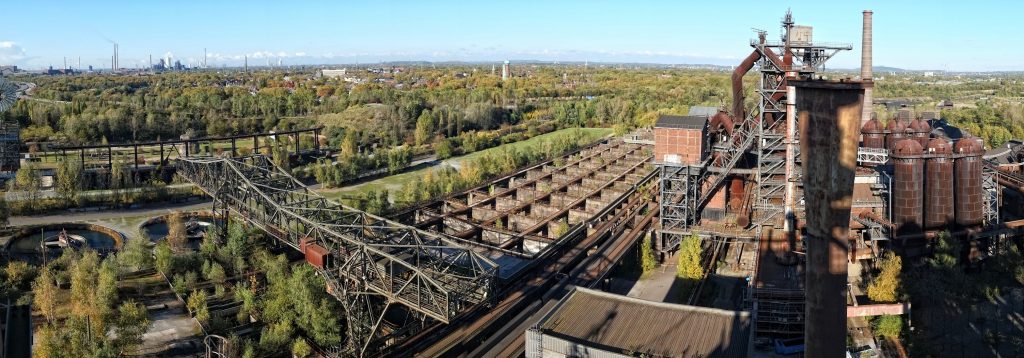

I think this (From Niemann & Schadler; ‘Post Industrial Urban Strategies’, 2012) neatly sums it up: “It might be that the deficits in frequently criticized modern urban design practices are less related to the quality of individual buildings but rather in the neglect of gaps and the spaces in between them.” There is an interesting unintended double meaning from the word ‘neglect’ there, for it is indeed when we neglect spaces that the best results sometimes happen: just as we create better ecosystems in our gardens by intervening less, I am fascinated by what happens when we do nothing. Left to its own devices nature does a pretty good job. Transport corridors for example, left virtually untended have been shown to have a much higher value for wildlife (particularly pollinators) than surrounding land, even where that land is low intervention agriculture. Often, the most interesting urban landscapes have occurred spontaneously in post-industrial environments, and some of the best approaches celebrate this rather than seeking to wipe it out and replace it with sleek granite and water features. Perhaps the most celebrated in recent years has been the Hi-line, because the way that it threads through communities catches the imagination. But for me, the Landschaftspark Duisburg-Nord by Pieter and Tilman Latz is really interesting.

Landschaftspark Duisburg-Nord

Tim Collins (interventions in the rust belt: the art and ecology of post-industrial space, 2000 ) suggested some good guiding principles:

Post-industrial public space should:

- Reveal the legacy of industrialism, not eradicate it or cloak it in nostalgia; create images and stories, which reveal both the effect and the cause of the legacy;

- Unveil social conflicts in the city, not repress them; create works that illuminate and explicate conflict and points of dynamic change;

- Reveal ecological processes at work in the city, not eradicate them; build infrastructure which embraces ecosystem processes and a philosophy of sustainability;

- Enable an equitable community dialogue, which envisions a future; produce new forms of critical discourse, which provide access, voice and a context in which to speak.

Which brings me on to permaculture. What is permaculture? It started from a principle first put forward by a New Zealand ecologist, Bill Mollison (and his student David Holmgren) who noticed that the greatest amount of useable biomass in terms of food was produced by multi-layered complex ecosystems such as forests. It has long since expanded to cover a whole philosophy of life and way of thinking. One of the interesting things about permaculture is its understanding of the importance of edges. Edge is king – the rougher the edge, the better. It is also worth looking at some of the more celebrated examples of brownfield site use along permaculture principles – Cuba.

Which brings me on to permaculture. What is permaculture? It started from a principle first put forward by a New Zealand ecologist, Bill Mollison (and his student David Holmgren) who noticed that the greatest amount of useable biomass in terms of food was produced by multi-layered complex ecosystems such as forests. It has long since expanded to cover a whole philosophy of life and way of thinking. One of the interesting things about permaculture is its understanding of the importance of edges. Edge is king – the rougher the edge, the better. It is also worth looking at some of the more celebrated examples of brownfield site use along permaculture principles – Cuba.

Salad crops grown in a central Havana organic garden. Note the simple raised beds made of concrete channels.

these Aloe are grown for medicinal purposes in this Central Havana Organoponica. Plant based medicines are common in Cuba.

These guys were really keen to show us around. Spot the tourist!

Cuba went through an almost complete socio-economic collapse in the early 1990s when the subsidised oil for sugar deals came to an end with the implosion of the Soviet Union. It lost 34% of its GDP over a fairly short period. Pesticides and artificial fertilisers were unavailable. All land was pressed into [organic] agricultural production, particularly in urban areas. Although many of these Organoponicas no longer survive, some still occupy the derelict spaces between buildings in meanwhile use. The benefits are huge. Apart from the obvious ecological and environmental ones, there are also community, education, food production, as well as health and well-being (you can read more about some of these Cuban Gardens in another post on this blog here). These principles can and are being applied throughout Europe and America. Anarchism and Community action have led to some exciting developments.

I am a trustee of a community Garden in my home town of Hitchin, near London. We simply took over a forgotten nettle-bound corner of the park: *, and after some initial suspicion from the local authority they are now enthusiastically behind the project. Fifteen years later, it now runs a community garden, two allotments and a resource building, employs several people, grows vegetables in several different projects with people with learning difficulties and runs sessions on wildlife, growing produce and other subjects. Community action should not be underestimated as a way of producing sustainable results. You can read much more about the Triangle community garden in another post on this blog here, or by visiting www.TriangleGarden.org)

I am a trustee of a community Garden in my home town of Hitchin, near London. We simply took over a forgotten nettle-bound corner of the park: *, and after some initial suspicion from the local authority they are now enthusiastically behind the project. Fifteen years later, it now runs a community garden, two allotments and a resource building, employs several people, grows vegetables in several different projects with people with learning difficulties and runs sessions on wildlife, growing produce and other subjects. Community action should not be underestimated as a way of producing sustainable results. You can read much more about the Triangle community garden in another post on this blog here, or by visiting www.TriangleGarden.org) So what of other edges? How can we ‘roughen up’ the edges of built structures? Well’ clearly ‘green cloaks’ are one option. Living walls, green roofs, etc. are all important and have a role to play. They cool buildings in the summer and insulate them in the winter. They reduce runoff, decrease CO2 both actually and in terms of emissions, have been shown to lower pollution levels, they provide food sources and increase biodiversity. A recent project at the south bank centre combines both – retrofitted ‘green roof’ on concrete terraces, run by a community garden and used by the public.

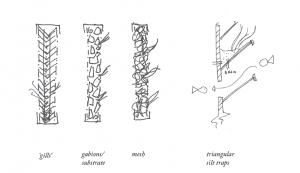

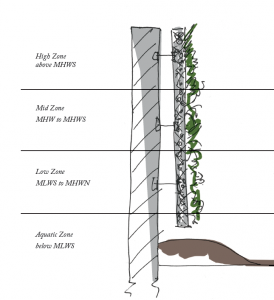

So what of other edges? How can we ‘roughen up’ the edges of built structures? Well’ clearly ‘green cloaks’ are one option. Living walls, green roofs, etc. are all important and have a role to play. They cool buildings in the summer and insulate them in the winter. They reduce runoff, decrease CO2 both actually and in terms of emissions, have been shown to lower pollution levels, they provide food sources and increase biodiversity. A recent project at the south bank centre combines both – retrofitted ‘green roof’ on concrete terraces, run by a community garden and used by the public.I was on Waterloo Bridge recently; as I walked across my pace slowed and I drew to a halt and gazed around. Of course it is virtually impossible to walk across that bridge without looking at the view, but what really struck me was not the undeniable grandeur and panorama of the city, or the sense of history laid out before me. It was instead the sense that the river is the forgotten part of all this. It is a truly wild thing flowing through the heart of a civilised city, which the bridges do no more than span. Jens Haendeler, a student working for me has come up with a novel solution for boosting diversity in river environments. Basically it is a system of crates containing a filling which can be populated (either directly or indirectly) with aquatic plants and fauna. This is the sort of creative thinking which we need to apply.

Concluding, I have included some shots (taken on my mobile phone, so forgive the quality) on a 15 minute walk along a canal through NE London last week. In a short stretch, many of the principles that I have talked about are demonstrated.

It will require action by all of us as professionals not only to design the positive responses to urban situations, but to consciously create spaces in which spontaneous reaction by either nature or community can occur.

These are opportunities, not problems to be solved.