Some of this piece is specific to contractors, some to designers; but much of it applies to both.

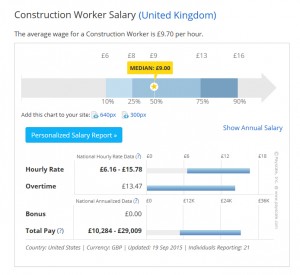

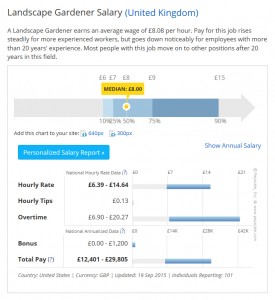

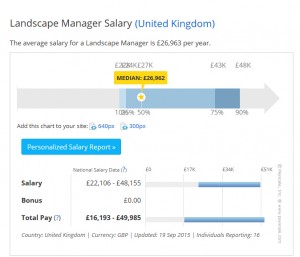

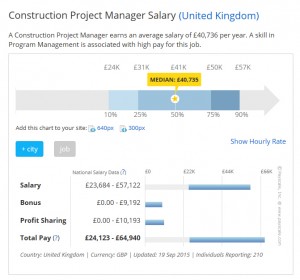

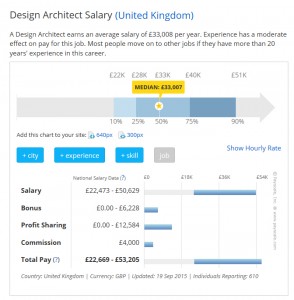

Do we work in an industry which undervalues itself and if so, why is that? Our nearest ‘neighbour’ is the construction industry. These figures speak for themselves: look at these comparisons between the various corresponding jobs in the construction and landscape sector (source: www.payscale.com).

Pay at site level seems to be linked more closely to agricultural pay than industrial pay. The higher up the management ladder you go, the bigger the pay gap becomes. Do we undersell our skills, or are they just undervalued by clients – is that the same thing? And what can we do about it?

Pay at site level seems to be linked more closely to agricultural pay than industrial pay. The higher up the management ladder you go, the bigger the pay gap becomes. Do we undersell our skills, or are they just undervalued by clients – is that the same thing? And what can we do about it?

Once we get locked into a price-driven market, various things start happening:

- Driving the price down is the main objective, so Margins are slim. This has various knock on effects:

- Pay is driven down. If pay is low then…

- Recruitment is difficult.

- And staff are Unhappy

- Slim margins mean Low Investment.

- Low investment and pay levels mean… Low Productivity… and

- More Accidents.

- Bad practices start to creep in: Sharp practices, hidden charges, commission, corruption, etc

Let’s look at the opposite process. If you are in a quality driven market, then:

- Quality is the main objective. The best way to drive up quality is…

- Invest more,

- Attract better staff, which means you have to…

- Pay better, and

- Train more, which means it makes sense to…

- Retain staff. To do this they have to be Happy.

The general view is that because of the tendering process, ‘cheapest is best’ is endemic. In fact, I am not sure that this is the case – it comes down to whether that market is price-driven or quality-driven. We regularly win both design and construction work in competitive tenders when we are not the cheapest. This is because experience, expertise, resources and general approach all play an important part in the selection process. The quality of the tender response is critical. Of course if the quality of the tender response is critical, then the quality of the request is equally important, or how else can a sensible appraisal be made? My impression is that over the last thirty years, tendering on the construction side has got sloppier. When I started in the industry, full Bills of Quantities were the norm in construction tenders, as were full construction package drawings. Tenders were delivered in unmarked identical sealed envelopes and opened simultaneously at a given time. These days they come in dribs and drabs, multiple extension of time are often the norm. What’s more, Bills of Quantities are a rarity (unless the contractor pays to have them done) and drawings have far less detail than they used to. One could view this state of affairs in two ways. Either it puts the contractor at a disadvantage because they are open to the sharp practices of their competitors – under-pricing tenders deliberately and then clawing back cost later – OR it puts the contractor in the driving seat because it allows them to deliver a higher quality service and work more closely with the client and design team. It all depends on the attitude (on both sides). John Melmoe of Willerby’s recently said to me ‘Price tendering is a thing of the past – it is dead’. Perhaps a bit of an exaggeration, but you can see where he is going. The bulk of his work is now achieved through partnering and negotiation. This achieves higher quality, shorter programmes, more profit and less conflict. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if the end result isn’t cheaper as well. But how do you break into a market like that? If established firms clean up all the work before it ever gets to tender, what hope is there for the others?

How do you know how much to charge – or put another way, what are the signs that you are not charging enough?

1 You have no time to market because you’re too busy serving clients

If you are constantly busy, running around after clients, working evenings to catch up – then you are not charging enough. Charging more will increase your returns, your quality of life and improve the quality of your clients – ones who appreciate you!

2 Your prospective clients compare you to someone else

If your clients are price shopping then you’re a commodity, and they are not seeing the value of your service. You quickly get sucked into the price-driven market cycle – not good!

3 Too many ‘Yes’s from practically every prospective client

If your hit rate is pushing 100%, then you’re not charging enough. Everyone likes a bargain and that’s what you are.

But other than the generalised statement of ‘moving to a quality led market’, what are the practical reasons for why you should charge more?

Here are a few:

- Not all your time is chargeable. If you are a garden designer or landscape architect, then this is particularly true. Probably only half your time, at most two-thirds can be charged for. Here’s the problem – in a 40-hour week, especially starting out, you’re going to spend half that week pounding the pavement (or more). You need to network, build your site/portfolio, blog, make phone calls, write proposals, and on and on. Once clients come in, you’ve got administrative work to do – somebody has to send the invoices, pay the taxes, and buy the toilet paper.

- Feast or famine. While you’re doing all that work you’ve got, who’s going to be doing the marketing, networking and getting the next job? Probably should be you – which means you’ll then have to take more time out doing that.

- Bills, Bills, Bills. As well as the rent, rates etc., there’s all those hidden costs – software, insurance, accountancy, coming here! Etc. etc. etc.

- Setting your own value. I bet you have something that you buy regularly, but only when it is on offer. If you make a habit of allowing others to negotiate your price down, or always expecting a discount, then it sends a message about how both they and you value your service. They will always try it on. You set the price – you set the value. If you want to offer a better deal, then don’t offer a discount. Drive a hard bargain for a decent price, but then over-deliver. That way the client will respect you but also think that you offer a really good service and recommend you. Getting a good price in the first place also allows you to be more flexible over small things that crop up along the way.

- You can only sell each day once. Consultancy and service industries are like hotel rooms – you can only sell your time once, and if you don’t sell it then it is lost for good. Your charges need to take account of this in two ways. Firstly, you need to cover for the down time, but also, when you are really busy you should sell the last bits more expensively. When customers book a hotel room or a flight, they always get a better deal when they book in advance online. Leave it till the day they travel and they’ll pay through the nose. It follows that you can charge more for last minute approaches by clients – and this is not unscrupulous – last minute rushes and running around are always disruptive.

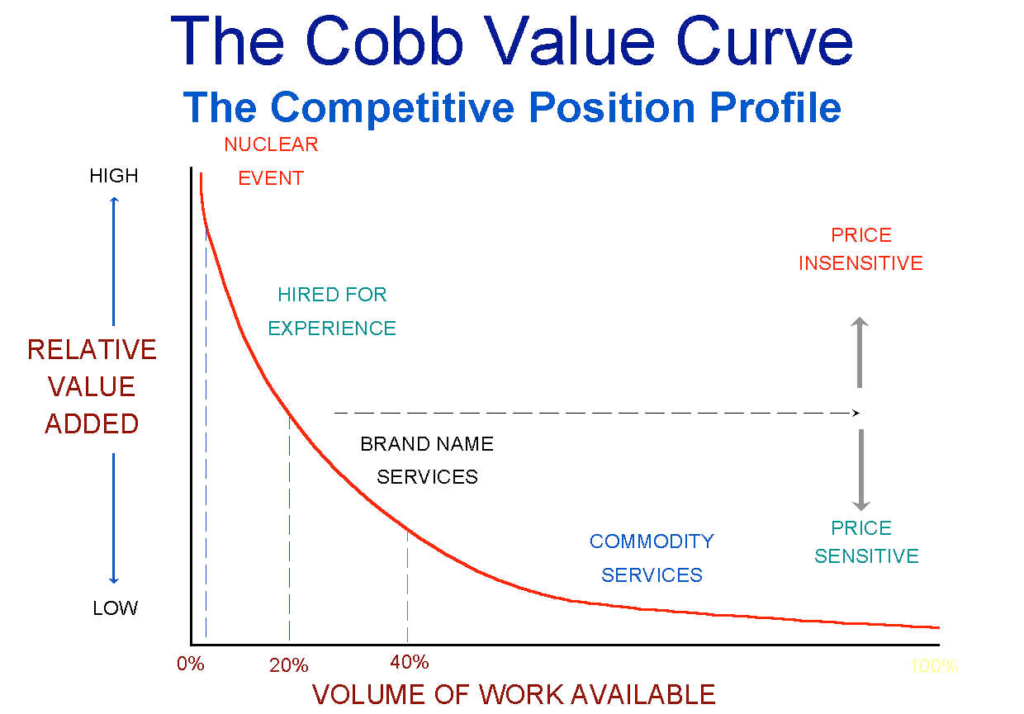

Look at this graph – it sheds some light on the relationship between value, price, and how a client sees the service they are buying. At the top is ‘Nuclear event’ – which basically means when a client has no choice but to hire you. This refers to the sort of service that you don’t have any real choice about and are not in a position to quibble about price – the business equivalent of calling the fire brigade. Bottom right is ‘Commodity services’ where you will be hired purely on the basis of price. The further to the bottom right you go, the less there is to distinguish between suppliers of service. The sweet spot is about 2/3 of the way up towards the left – ‘Hired for experience’, although you will notice that trusted brands also make an appearance.

Look at this graph – it sheds some light on the relationship between value, price, and how a client sees the service they are buying. At the top is ‘Nuclear event’ – which basically means when a client has no choice but to hire you. This refers to the sort of service that you don’t have any real choice about and are not in a position to quibble about price – the business equivalent of calling the fire brigade. Bottom right is ‘Commodity services’ where you will be hired purely on the basis of price. The further to the bottom right you go, the less there is to distinguish between suppliers of service. The sweet spot is about 2/3 of the way up towards the left – ‘Hired for experience’, although you will notice that trusted brands also make an appearance.

Along the way, let’s look at a few other practices that go on.

Commission

In the insurance industry, we are outraged when we learn that an insurer has passed our details on to someone else because they get a commission payment. What’s more, in foreign defence contracts and the like, such payments are classed as corruption. Why should it be alright therefore for a client to pay for a sculpture, piece of furniture or the like and the designer or contractor get a ‘secret’ payment? It’s not alright; it’s dishonest and lacks transparency. Don’t get me wrong – there is nothing wrong with an honest commercial mark-up – as a contractor you buy the furniture and you sell it to the client. Their contract is with you. If you are a garden designer and you take such payments, then you are either greedy or you’re not charging enough. Charge a decent rate and then you are free to recommend what works best rather than being tempted by whichever supplier pays you the most. And don’t be fooled; if it didn’t sway specifiers’ minds, then suppliers wouldn’t make such payments. (If you want to read more about this, I covered it in an earlier post in more detail: ‘Should Designers Take Commission Payments?’)

Who supplies what?

Should designers supply plants and other products? This is a difficult one – although many of you will probably already know my views on this – I have hardly made a secret of them. To my mind the process works best when it is crystal clear. It should be clear which part of the process the client is buying from which person, and who is responsible. In many ways, design and build is the clearest in this respect – there is only one person to go to when something goes wrong. That is how the world mostly works – if you buy a car or a telephone and something goes wrong, the manufacturer cannot blame ‘the designer’. However, let’s accept that that is not always possible or desirable to procure everything on this basis.

To me it seems obvious that the next best thing is if the client pays a reasonable price for the design part of the process and gets clear unbiased advice. The contractor then does the rest. The clue is in the name – the contractor does contracting and the designer does designing. In some cases, perhaps because the contractor doesn’t have the skills, or perhaps because the job is too small, it can make sense for the designer to supply the plants. But to my mind, this only works when the designer procures, supplies and actually carries out the planting. They are in fact then acting as a contractor, but it also makes the liability envelope clear should something go wrong. Otherwise the responsibility chain gets very tangled. What if a designer supplies the plant, but a contractor plants them and someone else is looking after them? See what I mean?

Clawback

I’ve touched on this earlier. However, I’d like to explore it in a little more detail. At the point of awarding a contract, the client is in the maximum position of power. The (prospective) contractor wants the job and there is always the real possibility that if he doesn’t jump through hoops, then the client will go to the next cheapest on the list. It is of course not in the client’s longer term interest to force the price down at this point, and this is one of the drawbacks of the tendering process when price driven. Because once the contract is awarded and the work is well underway, the boot is on the other foot. It is too difficult and expensive for the client to kick the contractor off site. Generally, he wants to get the job finished as soon as possible, which requires the co-operation of the contractor. At this point the contractor has the scope to make hay – charge more or less what he wants for extras and variations and claw back all that money he artificially cut from the tender in the first place. Both practices are short-sighted and unethical. How do we protect ourselves against this? Work with good consultants and reputable clients and don’t get drawn into these games. And don’t expect to win every job. It is always possible for someone to undercut you, but it frequently means they can’t deliver a good quality product or service, so the practice is not really sustainable in the longer term.

So… in summary it is best to be:

Clear

Quotations and proposals should be clear and unequivocal and make a good basis for any future variation. Drawings and specifications should be well defined, comprehensible and unambiguous.

Honest and fair

… even when there are easy opportunities to be otherwise. This is the only way to earn respect and build a business.

Compete on quality, not price

That way you get the sort of clients you want and a decent return for what you do.

(This piece was originally delivered as a talk at FutureScape in November 2015.)