(This blog is the first from Jeff Stephenson, head of Bowles & Wyer’s Aftercare and Gardening division)

From a driveway on the outskirts of Berkhamsted to the chalk seas of the Upper Cretaceous;

When you walk into a garden, do you ever think about where everything originated from? You might find plants from such diverse places as the swamps and wetlands of the Kamchatka Peninsula (e.g. Lysichiton camtschatcensis), the prairies of eastern North America (e.g. Echinacea purpurea) or the coastal forests of Chile (e.g. Fascicularia bicolor). That’s just the chlorophyll containing contingency; what about the supporting cast of hard features; decking materials, manufactured corten steel edgings and natural stones?

In this blog I’m going to concentrate on one of the most unglamorous and overlooked materials we use in gardens. It has been a mainstay material for infilling drainage channels, adding to compost mixes, covering driveways and paths or incorporating into traditionally crafted, regional, walls. I’m going to share with you what I know about flint. Before I took up horticulture, long before I joined Bowles & Wyer, I studied natural sciences; geology was and still is a particular interest of mine; so when I go into gardens I’m not just thinking about gardening, I’ve also got one eye out for the past; the vast expanse of the geological past.

Flint driveway in a Hertfordshire garden.

Knapped flint wall in a garden in Berkshire.

The flint that you would handle as a landscaper has much more dynamic origins then simply being extracted, graded and bagged. It originates way, way back, over 65-90 million years (Ma) ago during the Late Cretaceous Period; a time when, on land, Tyrannosaurus rex was stalking it’s prey, ancient bees were pollinating the first flowering plants; and in the sea, gigantic mosasaurs swam amongst ammonites and sharks.

What is flint?

This is the scientific bit; Flint is a particular type of chert that is specifically found in the chalk deposits of the Upper Cretaceous. It is made from the mineral chalcedony, an opaque, unified coloured and cryptocrystalline (micro crystal) form of silica.

What is chalk?

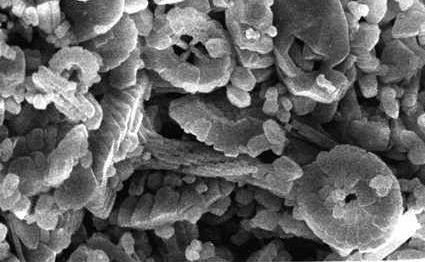

To talk fully about flint, I first have to discuss it’s bedfellow chalk. Have you ever walked atop the White Cliffs of Dover or around Beachy Head? Well the rock you’re standing on is chalk. If you were to take a piece of this chalk, crush it and view the pieces under a microscope you’d find rather unusual disc shaped structures called coccoliths. These were once part of tiny spherical units called coccospheres; the hard calcareous (calcium carbonate) skeletons of billions of microscopic organisms called coccolithophores, a type of marine plankton (they can still be found in parts of the oceans today).

They lived in the upper sunlit reaches of the Cretaceous sea. During this time the supercontinent Pangaea was breaking apart and volcanic activity was producing greenhouse gases which, through increasing global temperatures, prevented the formation of polar ice; leading to elevated sea levels. As they died they would have ‘rained’ down onto the sea floor forming a lime mud. These sediments eventually compacted into chalk.

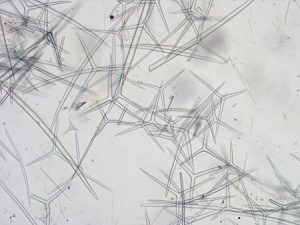

Sponge spicules under a light microscope.

Scanning Electron Micrograph of Coccolith plates in Upper Cretaceous Chalk.

How did the flint form in the chalk?

Take a closer look at those chalk cliffs; interspersed in dark hard bands you will find the garden familiar flint. But where did it come from? From a rather unexpected source. Living on the ancient sea floor were sponges whose bodies contained silica in the form of tiny needle like structures called spicules. It is mainly the silica from these spicules which, upon the death and burial of the sponges, broke down and enriched the water in the pore spaces of the buried sediments.

These siliceous rich waters then migrated along bedding planes and precipitated out in burrows made by the activity of organisms such as shellfish, sea urchins and worms. Over time and with further burial this material becomes flint. Millions of years of this cyclical process led to the accumulation of chalk deposits within which regular flint bands are found.

How did the flint get separated?

This is where plate tectonics comes in; movements of the earth’s plates (leading to the formation of the Alps) caused the uplift and exposure of these deposits which were then subjected to weathering and erosion. The chalk degrades but the hard resistant flint material gets eroded and re-deposited a number of times through the activity of seas, rivers and glaciers and can be found in numerous deposits laid down during the Tertiary and Quaternary Periods (65 million years ago to present). This is particularly evident along a number of beaches around our coastline.

The most recent part of it’s journey is via human activities; quarrying and extraction.

Flints reworked into beach deposits.

Chalk cliffs containing nodular flint bands.

So from a journey of over 70 million years ago in seas where mosasaurs once swam, to a designed driveway to keep your car on; flint has a story all of its own. You’ll never look at it in quite the same way again.

Jeff Stephenson