As this project has recently received some press and won the UK Society of Garden Designers Award for Public and Commercial space, I wanted to share something of the design process, particularly as it is an unusual design.

We were approached by Northacre PLC in 2008 to advise them on proposals for a new property they had acquired near London’s Lancaster Gate. It was the surviving arm of what had originally been two identical terraces, and was divided from Bayswater Road by a garden approximately 120m long, but only 15m wide. The building had a fine stuccoed façade – said to be the longest continuous stucco façade in Europe – which lent a flamboyant feel. I was reminded of the grand promenade buildings in Brighton, where I had often stayed as a child. But here, instead of facing out to the sea, the building looks over Hyde Park.

One of the sea front hotels on the Corniche in Cannes that influenced the architect in the mid C19th.

When I began to research the history of the building, I discovered that the architect was a big fan of French architecture and had indeed been influenced by the grand hotels of the Corniche in Cannes. I came across an early stereoscopic photo of the development, taken in the 1850s, just after it was built and the street trees were planted. Before that, it had been locally-famous as pleasure gardens, so it seemed appropriate to recreate gardens there again. As well as this flamboyant character, the building had something of the self-assured solidity of the Victorian era: confidently decorated and built to last.

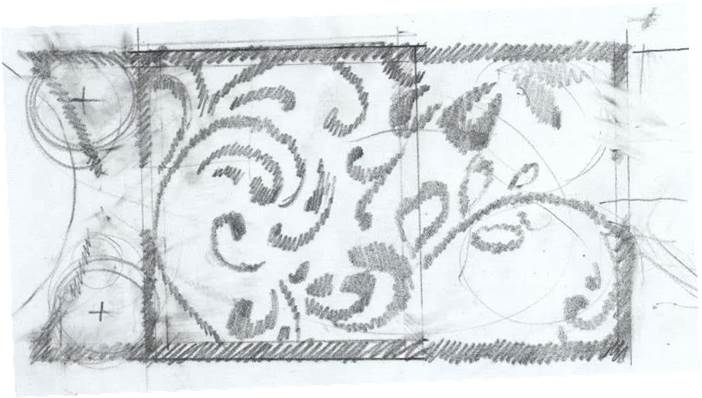

A couple of early sketches for the scheme showing the genesis of the patterns.

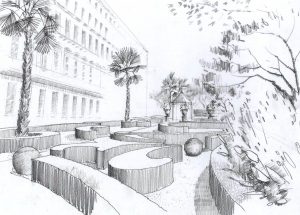

An early sketch of the scheme.

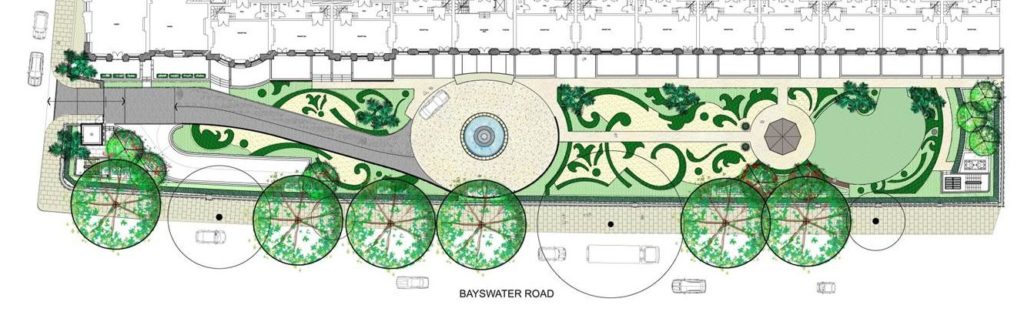

A design began to emerge in my mind. I leafed through books of late Victorian patterns – fascinated by stylised leaf and flower forms in swirling motifs. I developed a design based on these motifs – cut up, blown up on the photocopier, twisted and repositioned so that they rippled down the length of the garden in an undisciplined, freeform parterre. To give a vertical link with the building, and as a nod to the Corniche at Cannes, I placed a series of 6-8m fan palms along the back of the garden, punctuating the façade of the building. The design was finished, now all I had to do was convince the client. I made an appointment and turned up at the developer’s office. I sat in the meeting room with the head of architecture, the chairman and the development director, and went through the presentation I had prepared, slowly telling the story before showing the final plan. A long silence. “Absolutely f@#*ing brilliant” the chairman said slowly in his strong Swedish accent. Then he called the whole office in (nearly 40 people) and made me go through the whole thing again. In the end, they based the marketing of the development around the landscape and used the palm trees as the logo for the development.

The final plan. The free form shapes of the Buxus hedge swirl down the length of the terrace.

Preformed steel edges made it easier to form the shapes on site

Getting it built was another matter. How on earth to translate a drawing like this into a scheme? Eventually after much discussion, we decided to pre-form all the complex shapes in steel, so that they could then be planted as a box parterre on site. This worked OK, particularly as there was some flexibility in actual positioning of them. The next problem was the build-up over the roof slab. To start with, we had a 300mm drainage blanket of gravel to act as attenuation. Then beneath the planting, following advice from Tim O’Hare, we had layers of graded washed sand topped with a layer of rootzone material. This was a sand-rich growing medium with good drainage properties and some added fertiliser and organic matter. The whole lot was free-draining, non-compacting and well aerated. We insisted on test certificates for everything. All the specimen plants were pre-tagged and we had a short-list of nurseries that contractors could buy the other material from.

The final result was just as we had envisaged it. It was a long wait to see it finished, but it was worth it. There was no doubt that the constant support of the client was a major factor in realising the scheme.

A view looking west down the garden

The lawn at the eastern end of the garden.