Image copyright Ketih Hornblower, commissioned by Bowles & Wyer for a garden in Surrey

I recently was asked to give a talk at the landscape show on the subject of Master-planning country estates and large gardens – what do you do when confronted by several acres and an expectant client?

Estate master-planning is an area in which Bowles & Wyer have considerable experience, built up particularly over the last decade or so, in this country and internationally. So, question 1 –

What is master-planning? And how is it different from design?

There is often confusion about the differences between design and master-planning. Many inexperienced designers approach a master plan in the same way they would a garden design – they do some analysis, but often quite quickly get bogged down in shape making and fail to think radically about what is needed – they think in terms of features and style rather than areas and networks.

-

- Masterplans establish a framework of land use spaces or zones, connected by a distribution network. It is within this framework that design occurs.

Which leads us naturally to question 2 –

What processes should you go through to masterplan a site?

There are three basic stages – Information gathering, Analysis and Design. Remember the S-A-D process you were taught at college? This applies doubly to landscape (or any) master-planning. There is a fourth process that overlays this, which is stakeholder engagement. In the public realm this is a continuous and multi-layered procedure. However, for private projects, although important, it is more straightforward.

1. Information gathering stage

Magic maps (https://magic.defra.gov.uk/) can be a really useful resource in desk surveys.

- Before you go to site, before you start on anything else, it is good to carry out a thorough desktop study into background information. Web-based sources like magic map are useful for this – look at designations, neighbouring land uses, local planning applications, planning history, etc.

- The next step obviously is to Visit the site: spend as much time there as possible. Walk around the whole area and take lots of photos.

- Talk to people who know the site well. Obviously, this may include the owner, but also site managers, gardeners, people who have had previous dealings there (other designers, tree surgeons, local authority officers etc.). This information can be invaluable.

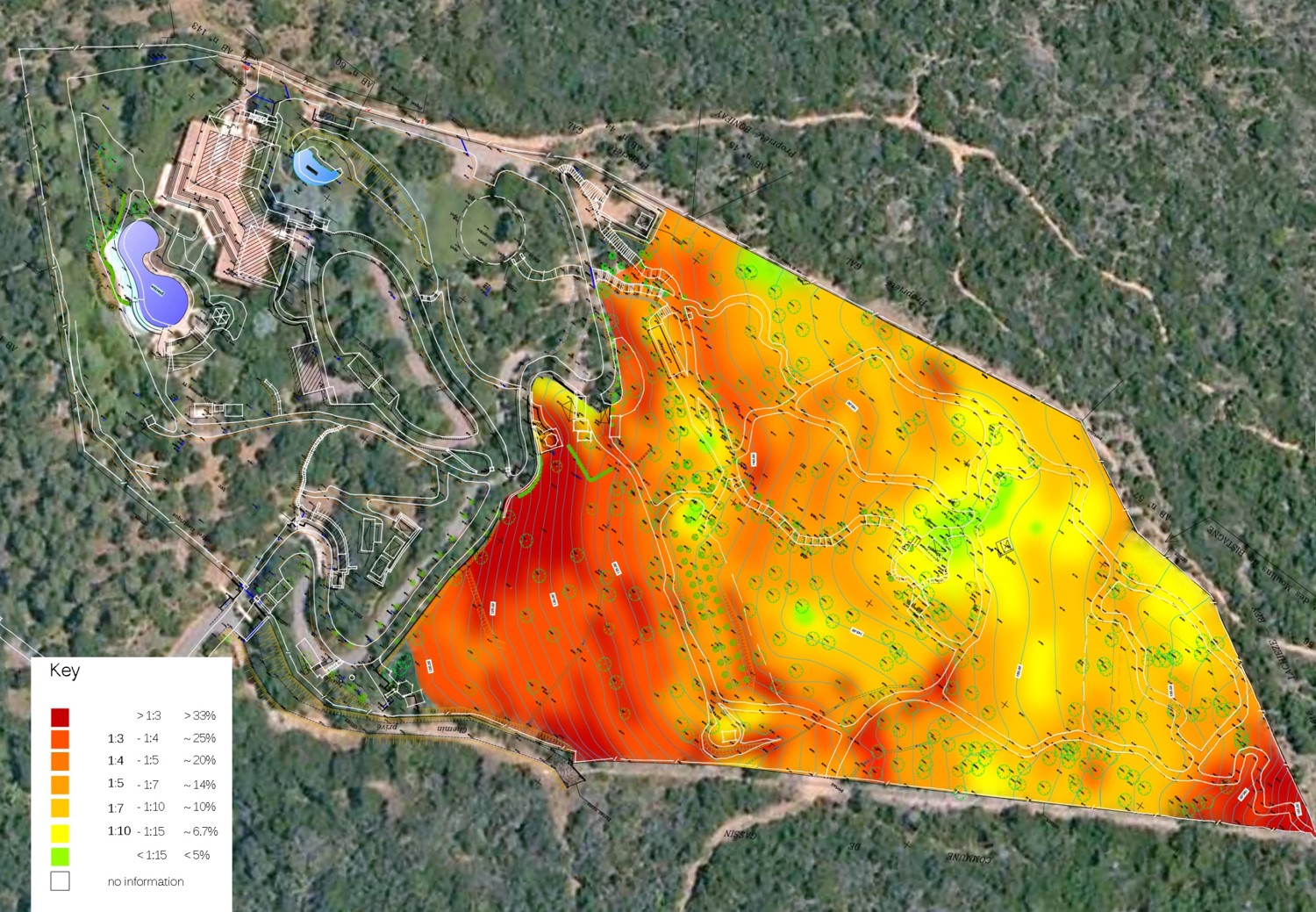

This is a slope analysis for a site we master-planned in the south of France – the red areas show the steepest slopes.

- Again this may seem obvious, but Aspect and topography are crucial – they have a major bearing on almost everything. Resist the temptation to start formulating design solutions until all the information is analysed and collated. In most cases, aspect and topography are likely to be bigger drivers of the final masterplan than the client brief.

- Use aerial or satellite photography

- Look back at previous cached satellite/aerial pics to get an idea of history/change on the site. This is not always easy, but can be really useful.

- Sometimes useful for looking at seasonal change – not all photographs are taken at the same time of year.

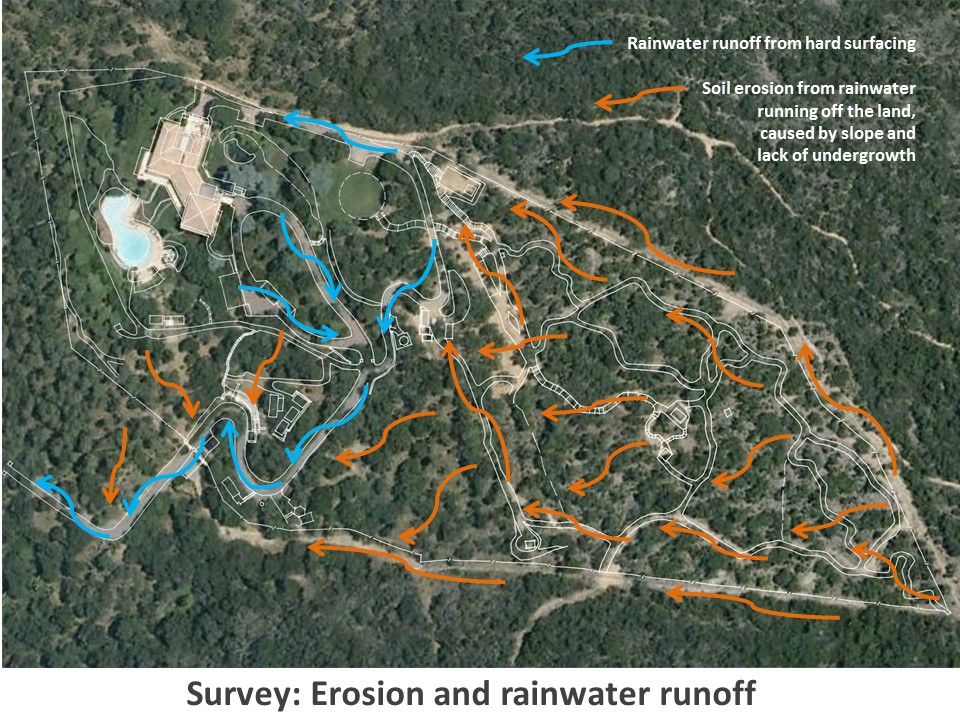

- Combine overlays and aerial photography – we find this a really useful methodology and it makes sure that your design process is always pinned back to site.

- Other Surveys may also be useful:

- Commission a tree survey if possible, or in the case of a woodland a walking woodland health survey. Generally very useful, although sometimes you have to convince the client to spend the money.

- Commission ecological survey information – especially if there is a lot of semi-wild (or wild) landscape.

- Hydrological information – if Hydrology or drainage are an issue, then this is vital in formulating solutions.

- If abroad, local climate

- What is the house going to be used for?

- Main residence – family use? Is it going to be a low-key home for the family?

- Holiday or country home? If so what are the times of year of visits?

- Entertaining (shooting, country house parties, etc)? How many guests and how often? Sometimes larger houses have to virtually function as hotels – if so, you need to consider this from the start.

2. Analysis stage

- What are the overriding physical constraints that affect the site?

- What further research is needed? Often a consideration of this stage throws up extra research that can be useful to undertake.

- What is the nature of the constraints?How can they be mitigated to meet the client brief?

- How are the client requirements going to impact on the site?

- How might these change over time?

- How might the various client uses have different impacts? Sometimes these can be in conflict – quiet family use and formal large-scale entertaining for example require a completely different approach.

- What land use zones need to be near the house and which can afford to be further afield? Swimming pools for example generally need to be near the house. Ditto kitchen gardens. Games pitches or tennis courts can be a little further away, whilst woodland walks, lake etc. can be quite distant.

- Budget and timescale

- What are the client’s time horizons (and are they realistic)?

- Are there overriding budget constraints? Although be warned, it is best not to get sucked into budgetary discussions too early.

- What future management or maintenance resources are likely to be available? This needs to be one of the earliest questions you ask.

- Context

- What bearing does the context of the site have on usage and design?

- How might land use on neighbouring plots change in the foreseeable future change and what are the implications? It is not uncommon for example to find neighbouring farmland under threat of future development – this has happened to us during the master planning process at least three times that I can think of.

- Analyse key views across the surrounding countryside, particularly from the house. These need to managed rather than just kept. Use clumps of trees or other objects to mask unwanted parts of a view.

3. Design Stage

- Access and distribution are important

- Look at the journey that visitors will make when approaching the house. Not all should be revealed at once – there should be a serial vision as to how the design unfolds.

- Think of day-to-day use by the family; this may well be different from guests.

- For larger houses in particular, think of servicing. Remember that a very large house with say 15-20 bedrooms acts like a hotel when full for a weekend or other event. There will need to be drop-off and parking for guests, parking for staff, but also separate access for food, drink laundry and other deliveries. This needs to work smoothly and as nearly as possible, invisibly.

- Security may be an important factor for some clients. This has a significant bearing on communications and distribution networks

- You will also need to think about how maintenance equipment (such as minitractors, mowers etc) move about the site.

- Uses:

- The internal and external uses need to be aligned. For example, main reception room and spilling out space; pool room and sun terraces. We had one project where the architect completely reworked the internal layout when we pointed out the potential of the views and west facing façade.

- Consider grouping uses together where feasible – entertaining or grander spaces, family use spaces, sports and outdoor activities (tennis, swimming, trampoline, play equipment etc.) There may be scope for spaces to have more than one use.

- Think about practicalities for gardeners – composting, equipment storage etc, but also WC and break facilities.

A Spectacular view from an estate in Hertfordshire – image copyright Quintin Lake

- Views and spaces

- Look to ‘manage’ key views. It may be that removal of some trees (or groups) may open beautiful views. Alternatively, there may be other features (pylons, buildings etc) that can be hidden by tree planting. Consider using landform for this as well, preferably combined with tree planting.

- Segues between spaces are crucial. This is particularly important where uses vary between spaces.

- Finally, style – this should be quite a long way down the list. Land use and practicality are much more important.