If you put the word ‘Urban’ into Google image search, this is what comes up:

A glossy, sleek, landscape of steel and glass. Actually, I think that many people’s idea of Urban is grittier, more individual; maybe even a little threatening. Something more like this:

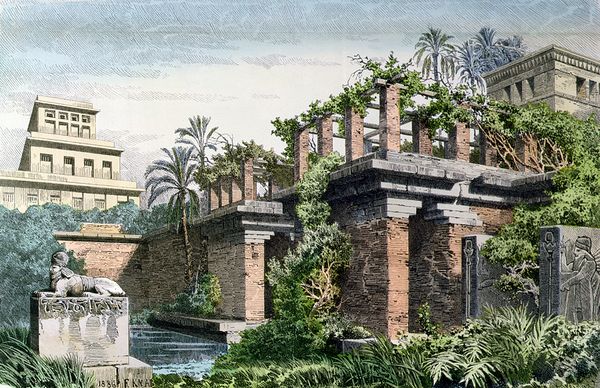

The truth is more interesting. Landscape and Urbanism are intimately linked. If you ask almost anyone what is the earliest example of garden design they can think of, they will probably say (other than Eden) the hanging Gardens of Babylon.

This is the only one of the seven ancient wonders of the world to have no known historical location, although it is almost certain to have been in what is now Iraq. The important point is that the very concept of gardens emerged at the same time as Urbanism. Cities only became possible because people moved from a nomadic hunter-gatherer existence to one of settled agriculture. The idea of making gardens emerged at the same time – gardens and buildings are inextricably linked; so one could argue that without cities there would have been no gardens.

Medieval cities were pretty dense – look at southern European examples that still survive. The same was true in a more haphazard way in Northern Europe, where wealth came later. Significant green urban spaces only began to emerge here with the Agrarian and then Industrial Revolutions, and the explosion of learning that came with them. Buildings began to be taller, partly because of new building methods. Larger scale developments began to emerge, along with ideas of urban design and town planning. These higher densities created value which effectively funded green spaces between the buildings: much of central London with its squares was built in this way. I love this image of Belgrave Square, a chunk of woodland surrounded by a dense urban grain:

This trend continued into the twentieth century. Look at this wonderful example of Urban design from Darbourne and Darke in Lillington Street, Pimlico. This was the project that inspired me to go into Landscape Architecture in the 1970s. Once again, the buildings justify (or perhaps are justified by) the landscape spaces between. Is this buildings in a landscape or landscape between buildings?

We have tried to follow this route with our own work. Look at this example of dense Urban development in St Johns Wood, below. It is easy to grasp the scale of the space and the way it is shoe-horned (over an underground car park) into a sliver of land between new houses and the back of the adjacent C19th houses.

And finally, Singapore. Some of you might remember from James Wong’s barnstorming presentation at the ‘Exotic’ conference in spring 2014 his fantastic images of ‘greened’ urban development in Singapore:

Here, they seem to have the daring to achieve the sort of things that British Cities achieved in the Victorian era. In our own way, we are still making daring statements in London, such as this huge living wall on the Rubens Hotel designed by Gary Grant.

This tied in very neatly with one of the co-sponsors of the conference, Treebox, whose system for living walls has the lowest water and nutrient usage of just about any on the market.

Perhaps the biggest challenge in Northern Europe though is how to deal with the post-industrial age. Nature has its own way of doing this of course. Look at this picture of a deserted, derelict Aldgate East tube station:

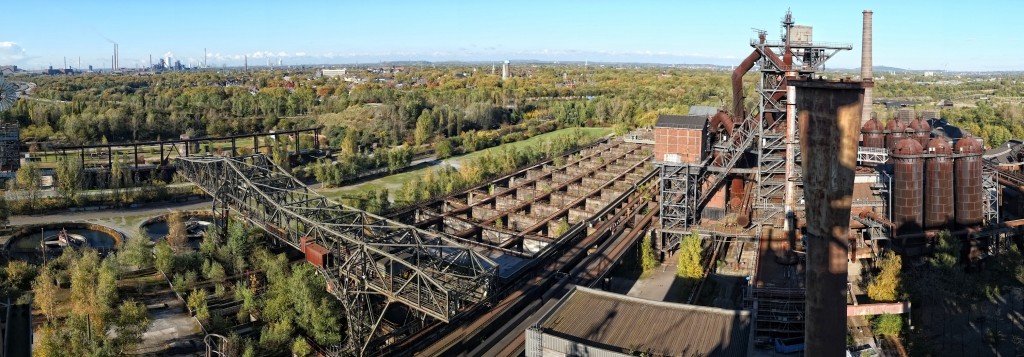

Duisberg in Germany (by Latz and Partners) is the best known of these post industrial landscapes. Here the gutsy nature of the industrial structures was retained rather than being sanitised, and a series of contemporary uses was found for the former steelworks.

Partick Cullina explored this more fully in his fascinating presentation on the New York Hi-Line Park. This landmark project came about through the intervention of residents when the structure was threatened by demolition, and a design competition was staged. It was won by a Briton, James Corner, a graduate of Manchester Poly like me. There is no doubt though, that the real success of the project is Piet Oudolf and Patrick Cullina’s subtle herbaceous planting.

‘Grand Projets’ have their place here too, and there is room for both these and the post-industrial renovations like the Hi-Line. Dan Pearson and Thomas Heatherwick’s Green Bridge project in London promises not only to be a fantastic structure and addition to London’s skyline, but also a major regenerative engine in its own right.

However, cities are as much about anarchy and the individual as government (perhaps more so?). So within the city grain there is room for outbreaks of individualism. I love London’s city farms such as Mudchute. Who could ask for a better picture than this:

However, cities are as much about anarchy and the individual as government (perhaps more so?). So within the city grain there is room for outbreaks of individualism. I love London’s city farms such as Mudchute. Who could ask for a better picture than this:There are also hundreds, thousands, hundreds of thousands of tiny back gardens, each crammed with plants and artefacts in an orgy of individualism and biodiversity. James Fraser’s anarchic gardens perfectly represent the importance of small interventions. These are perhaps more important for the ‘green life’ of a city and together make up the mosaic that is its true character. Here we can all play a part, and particularly the garden design community. Sue Illman talked passionately about the way water (as an issue) links all landscape spaces. How we manage water resources and how that influences the design decisions we make, thus becomes very important. She mentioned CIRIA and its C697 paper (downloadable for free) as a particular resource in this respect, and although some of the thinking has expanded a little since then, it is still a useful source of information.

The true nature of cities therefore begins to emerge; far from being sterile hard environments, they are as much made up of a network of vegetated spaces running through and between the buildings. In fact, more than 50% of London’s area is either ‘green’ or ‘blue’ (water). If we go back to aerial photographs, look first at this picture of Central London, and then one of the whole of London.

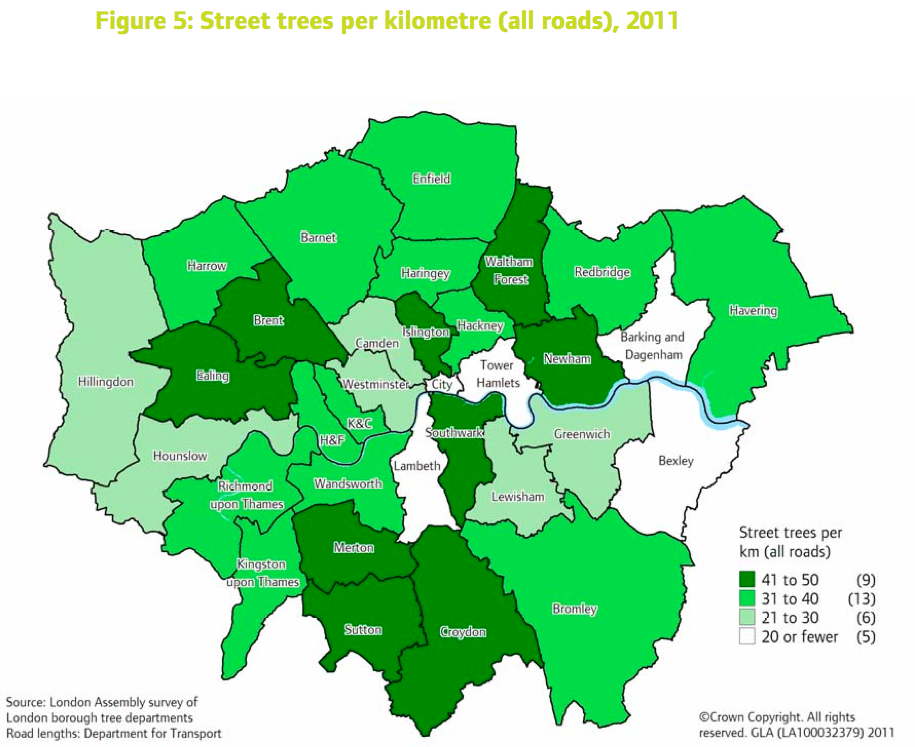

It is noticeable from these just how green the London is; it is not just the capital however, Manchester, Sheffield, Bristol, Glasgow and many others are just as green. The world’s largest urban horticultural survey (iTree) was undertaken in London this summer in an attempt to quantify cost and other benefits accruing from trees in the city. And there are many; look at the map below of the density of street trees in the London boroughs from the GLA website. What comes through is not only some of the surprising boroughs (like Southwark, with 50 trees per km of street) but also how haphazard the pattern is: it does not follow the ‘green doughnut’ that one would expect. Investment makes a real difference here.

I think what was remarkable about this conference was that at a day devoted to ‘Urban’ we spent the whole time talking about plants and nature. Our most important actions are to create the framework; nature will do most of the work thereafter. Indeed, one of the most interesting threads to emerge from the day was the way in which all the speakers worked with rather than against nature. Sue Illman’s rain gardens, Patrick Cullina’s planting on the Hi-line, James Fraser’s forest gardens and Dan Pearson’s carefully poised plant communities all had the underlying principles of permaculture in common. As Patrick Cullina pointed out, our interventions are important but they need to be finely balanced.

The SGD owes a particular vote of thanks to both Treebox and Griffin Nurseries for their generous sponsorship of this conference. We shouldn’t forget that planting can’t happen without nurseries!

Speakers details:

- Chairman: John Wyer CMLI FSGD, Bowles & Wyer: www.bowleswyer.co.uk

- Sue Illman PPLI director of Illman-Young and immediate past president of the Landscape Institute. www.illman–young.com

- Patrick Cullina, former director of horticulture at both Brooklyn Botanic Garden and the Hi-Line. Patrick Cullina Horticultural Design & Consulting 894 Sixth Avenue, 5th floor New York, NY 10001 [email protected]

- James Fraser, The Avant Gardener, www.avantgardener.co.uk

- Dan Pearson FSGD, www.danpearsonstudio.com